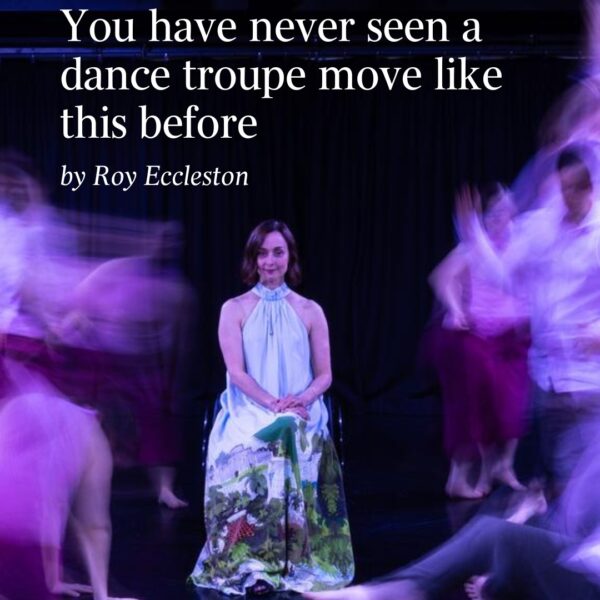

Restless Dance Theatre’s Michelle Ryan is intent on blowing away prejudices

By Roy Eccleston from The Australian

From her wheelchair, Michelle Ryan bends towards her father in his Townsville hospital bed. John Ryan is dying, although until now the 85-year-old hasn’t acknowledged it. “You’ll never know how much I love you,” he tells his only daughter. And then, as their foreheads touch, he gives her the truth: “Shelly, I don’t think I’ve got long.”

“I know, Dad,” whispers the former star dancer and now artistic director of Adelaide’s trailblazing Restless Dance Theatre. Within a few days John is dead, followed 10 months later, in November last year, by Ryan’s mother Lynda. Suddenly Townsville, where she has been raised, married and divorced, is home only to memories.

Ryan, whose stage career was guillotined by a shock diagnosis of multiple sclerosis at just 30, takes her pain back to South Australia. Then, with more tears and other traumas, she weaves it into art. The result is the 52-year-old’s contemporary dance work Exposed, exploring themes of fear, loss of control and trust, to be performed at the Sydney Opera House from August 30 by Restless, a professional company intent on blowing away prejudices about people with disabilities.

For the seven dancers, four of whom have Down syndrome, the show on the nation’s most prestigious stage will be the pinnacle of their careers. For Ryan, who performed at the Opera House while a principal artist with Meryl Tankard’s Australian Dance Theatre in the 1990s, it will be a chance to show how far the company has come since the Australia Council almost killed it in 2020 by rejecting a four-year funding grant.

For audiences it will be an opportunity to see a diversity of dancers chosen for their personalities rather than physiques. “Our dancers don’t look like stereotypical dancers, but it’s actually in their difference I see beauty,” Ryan says. “And that’s what I hope other people see. There is so much talk about diversity and representation – that’s why I think this is such an important company. They show vulnerability and relationships in a way that is really strong. They are completely uninhibited. And they still have high skill levels because they’re trained by the best.”

In one poignant duet, dancer Michael Hodyl, who has Down syndrome, comes to the aid of Michael Noble, who has no disability, in a choreographed reconstruction of that moment in the Townsville hospital ward. Ryan explained its genesis to her performers and the composers who wrote the music for the work. When the dancers’ foreheads touch, she often sheds a quiet tear.

“Do you remember I was a bit sad, and I wanted to make something beautiful for my Dad?” she says as we talk with Hodyl, who channels her in that moment on stage. “It was my inspiration,” he says after some thought. “It makes me feel what Michelle went through with her father.” In this case, though, the outcome is different. Noble’s character does not die but is revived by love. “I care about him,” says Hodyl about his role. “I lift his neck … and then I stroke him. ‘Are you alright?’”

“A lot of the work that we create here comes from the idea of, ‘What do you want the heart to say?’,” says Ryan. “Exposed is about who do you trust, and how you don’t know who’s got your back.” It is also about being rejected and finding your way back through the embrace of others. That, she says, is a subject she knows very well.

In 2012 Ryan spotted an advertisement for the only job she felt could lure her back into the professional arts world: artistic director at Restless. Given its embrace of disability, she knew she had something to offer. She had been one of the country’s finest contemporary dancers working at the Australian Dance Theatre in the ’90s, but she also knew firsthand how cruel life could be for those with disability.

In Belgium while practising ballet one morning in 2001, Ryan realised her calves were touching but she could not feel them. After a physiotherapist advised her to seek expert advice, she saw a neurologist whose diagnosis stunned her. She knew little of MS, in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the sheath protecting nerves. It is the most common acquired neurological disease for young adults, and most likely to affect women.

But she did know her symptoms meant she could no longer trust her body to dance. Over six months she went from walking, to walking stick, to wheelchair. “It took away my identity and my job, everything, with one fell swoop,” she recalls. “I stopped dancing on that day.”

The years that followed were a rollercoaster ride. Ryan managed to return to using a walking stick for a time, married in 2003, helped run the Townsville arts company Dancenorth, but five years later was devastated when the marriage ended. “I’d reinvented myself once,” she says. “Now I had to reinvent myself again.”

She began by rejecting the arts world. “I had been around so much in that environment of selfish people that I needed to get out,” she says. “I needed to be around people who were making a difference.”

Ryan found a job in Brisbane working with people with disabilities. “And I saw how much they struggle and how under-represented they are,” she says. “And always feeling that you are lesser than other people. But I saw good people trying to make a difference.”

No longer considering herself a dancer, she understood that feeling of being devalued. But then, in 2011, she was asked to perform a three-minute solo at the Brisbane Festival by Belgian choreographer Alain Platel. Ryan told him she had not danced for 10 years, used a walking stick, and feared she would fall over. “And he said, ‘Well, wouldn’t you just get up and keep going?’ And that just really changed my thinking at that time.” She took her stick, walked slowly up onto the stage, and performed an “arm dance” while sitting on a chair. “It felt fantastic, I felt like everyone just disappeared and I could do my dance. And then I was surprised at the end that people clapped.”

Later, Platel challenged her: “Why don’t you dance anymore? You’re a dancer.” She asked who would want to watch someone like her onstage. “And he said, ‘Well, I think 300 people just enjoyed having you onstage’,” she recalls.

“It really changed my whole thinking about myself and about the importance of artists with disability. And it really gave me a fire in my belly to go, ‘I’ve felt worthless for 10 years, and I don’t want anyone else to feel like that’.” She began to fall back in love with dance, and perhaps herself. The disease had weakened her physically, but there was strength inside.

In 2012 she was performing in Adelaide when the Restless job became available. “I thought it was the perfect kind of match,” she says. “Restless was the only company that I was prepared to come back to the arts for. Because I just felt like we could make a change here and hopefully start to make people question their perceptions of disability and inclusion – and that we’re all people, so why do we have these labels?”

Restless had been an innovative local company but tended to do few shows, and those mostly for family and friends. Ryan, who started in 2013, had three goals. First, she wanted to “schmick up” the company with dramatic photographic displays of performances and dancers, to project an image of quality and give it the value it deserved. Second, she wanted Restless to perform at the Adelaide Festival, which had never happened before. Third, she wanted to take the company on tour.

All were achieved, with three performances in five years at the festival, and tours to Seoul in South Korea, Brisbane, Melbourne, regional towns and soon, the Sydney Opera House, Hobart Theatre Royal and Seoul again. Ryan, who works closely with creative producer and former dancer Roz Hervey on devising shows, made the company professional, paying a wage to the core of seven dancers. At least three days a week of studio work, under former Australian Dance Theatre member Larissa McGowan, was also introduced.

The result was “we got a very different audience”, she says. Each performance had just 10 people watching, but the dancers did 60 shows. The idea came from her own observations – she lived near a big hotel, often had a drink there, and yet in three or four years had only seen one person with Down syndrome there. She wanted to put dancers in public spaces so people might randomly walk by and hopefully question, “Who can dance and who can make art?”

At first, much of the reaction was “Oh wow, they can actually dance,” Ryan says. “What I would love from audiences is that they expect excellence and not to be surprised by it.”

While she wants to influence society’s thinking on disability and labelling, she prefers a subtle approach. “I love to lure an audience into a nice, safe, beautiful world but then have something that makes you question. In Intimate Space we had a beautiful duet on the stairs in the Hilton – Jianna Georgiou [who has Down syndrome] with dancer Alexis Luke, who doesn’t appear to have disability. If you’re an audience member you’ve got headphones on and all you can hear are judgments whispered, like ‘Should they be together?’, ‘Surely he can do better’, and ‘Should they be able to get a room?’” In another scene, a couple with disabilities lay in bed together with the audience watching by torchlight. Again, it provoked questions.

The direction in which Ryan was taking Restless won applause and support. Major philanthropic trust the James and Diana Ramsay Foundation became a backer, providing more than $450,000 to Restless, starting in 2018, the year after Intimate Space. The support helped pay for staff and helped Ryan travel to art – markets to “sell” the shows. A grant to the Adelaide Festival helped Restless perform its show Guttered at the 2021 Festival.

Guttered, set in a bowling alley, took aim at the idea that people with disabilities should not have to face challenges, such as by the use of gutter guards in bowling alleys to keep the ball rolling towards the pins. Ryan supports the concept of the “dignity of risk” from her time working with disability in Brisbane. Well-intended safety nets can cause more harm than good, she believes. “I can tell you,” she says of her dancers, “they can all bowl.”

Ryan believes that failure and mistakes are an important part of life and learning. All her dancers are given correction, not as criticism but for improvement. The approach has paid off: in 2018 and 2019 Restless was nominated for consecutive Helpmann Awards, and while it did not win, was one of just four finalists with the Australian Ballet, Sydney Dance Company and Bangarra Dance Theatre.

One of Ryan’s crowning career moments came in 2020 when she won the Australia Council Award for Dance and was lauded for using her lived experience of disability to inform her work “with humour, warmth and searing honesty”. She accepted her award in her wheelchair and afterwards Georgiou and Luke performed a duet for the audience at the glittering function.

But within weeks, the Australia Council ended its $300,000 annual funding for Restless, rejecting its grant application for the following four years. Ryan felt betrayed. “It was quite a shock,” she says. “I was angry that I felt like I had been wheeled out, like I was completely on display. I was like the poster girl – you know, ‘Look what we’ve done, we’ve given this mainstream award to someone with disability’. And I challenged them. But it couldn’t be changed. So losing the main bulk of our funding … we could easily have gone under.”

Since Ryan draws heavily on her own experiences when creating her shows, the Australia Council episode was, perhaps, more material for Exposed. But it was what happened when she returned home to Adelaide after one of her trips to see her ailing father in Townsville that really shook her.

Ryan, small and slim, wheelchair-bound, with a large piece of luggage, arrived from the airport by taxi to find the road to her apartment blocked. Since she lived beside a Covid isolation hotel, she assumed a busload of international passengers was due. Normally, the taxi could drive her to the door. This time, a police officer stopped the cab, telling her she could go in but only if she made her own way. Despite her pleas, tears, and eventually furious expletives, he refused to budge. She faced a difficult downhill run in the wheelchair with her suitcase. She told the officer it was “on you” if she hurt herself and asked for his help. “That’s not my job,” she says he replied. When she argued, she says he warned her he would arrest her for “threatening a police officer”. The taxi driver could not help, a worker at the hotel was told not to help, and “I was crying by this time”.

Up to a dozen other police stood watching. One told her if she wanted to make a complaint she could do so the following day. “And as he walked away, one of the other officers said to me, ‘I’d think about that before you make a complaint’,” Ryan says. “At that point I threw my suitcase on my lap and told them they were all f.cked. I’m bawling my eyes out. I’ve done both rotator cuffs in my shoulder [from heaving the bag]. I’m not the biggest person, I’m not threatening. I was literally asking for help. And he wouldn’t give it to me. I’d just left my Dad, who was in a really vulnerable position, and it just made me really question, when you ask for help does someone help you?”

Dancer Maddy Macera remembers Ryan using that experience when creating Exposed to quiz the company about when they felt frightened and vulnerable. She’s asked us things like, ‘When have you needed to ask for help? When have you felt safe? When have you felt unsafe? What situations are you in?’ And we tried to physicalise those. Someone said, ‘I feel safe when my back’s against the wall, you can see everything’. And there is this 10-minute piece in the work where we’re trying to get behind each other to kind of get a reaction from the other person.”

Macera, who joined Restless in 2021, says she had never worked with artists with disability before. “I know so many people that haven’t seen disability on stage or in the arts at all. And I think that’s super important. We need to be seeing that more.” The 29-year-old says she has learned a lot from her colleagues with disability. “They are really fun to work with,” she says. “They’ve taught me a lot about myself. They’ve taught me a lot about art and passion – they have so much passion for what they do. And I’m learning new things every day from them, watching them, how they work and how they figure out a creative task or physicalise something that Michelle has given us. It’s very interesting and rewarding to be in the same space as them. It’s actually given me a new way of looking at how people work and how people learn. It’s very cool to see different ways that people can take on a task.”

In these creative moments, Ryan says the dancers with disability often offer a surprising perspective. “It doesn’t have to be a physical response, it can be a comment,” she says. “And sometimes I’m like, ‘Whoa, where did that come from?’ But I love it. You know, a lot of dancers are trained in a certain way. But these guys use a lot of their own internal ways of moving to enhance the work. So even though they have technique as a base, it’s all about the way they move – and then how we find that common language together.”

Having a paid job with all the discipline and expectation inherent in that has opened up horizons for the dancers with disability. Some live independently; they all make their own way to the studio. Jianna Georgiou, 32, who joined in 2006 and has won a Ruby award – the top honour for SA artists – says dancing makes her excited and nervous. “It can be a bit hard for some people with disability but when I’m dancing I just feel different, calm and communicating with other people in the space,” she says. “It feels like I’m just in my own world.”

“Restless is all about giving us something very special in our hearts,” says her colleague Charlie Wilkins. The athletic 25-year-old spent almost all of 2022 working, with six shows around the country – a rare feat for any professional dancer – and is also a star swimmer who has represented Australia. “We’re all family here,” agrees Darcy Carpenter, 26, who moved from SA’s Riverland to Adelaide, determined to rise to the top ranks of the company. “I see Charlie as a brother, I see Jianna as a sister, I see Michelle as like a second mother to me.”

Hodyl, whose love affair with dance began when watching the film Strictly Ballroom and singer Ricky Martin, proclaims he is never nervous – ever. When he dances, he says, “I’m expressing my passion and of course my personality”. He pauses for a moment to think about his role in Exposed. “It’s one of those things that is not easy for me to explain,” he says, before adding: “My role is [being] part of the team I dance with.”

Does he enjoy the applause? “Yes, I’m happy and proud of myself.” He says dancing has transformed his outlook. “It’s changed me, changed my life. I’m more easy- going, more confident. I’m watching different movies now – romantic chick flicks!” Before, he says, he had been “a bit crazy for superheroes” and spending too much time with his AFL footy cards.

Hodyl says he has a disability with his speech – sometimes his enunciation is a little unclear. But dance provides a different language, and he hopes his performance can change minds. “It should inspire people with disabilities that they have a voice,” he says. “They need to have someone, for them to be included.” Ryan and Restless did that for him. Did he enjoy being challenged? “Not just being challenged but – exploring what I’m doing in the future.”

The work of Restless is inspirational, says Darryl Steff, the chief executive officer at Down Syndrome Australia, which advocates nationally and helps provide support to families and information on the chromosomal condition. “People with Down syndrome are like anyone else, they want the same things in terms of education, – employment, living on their own,” he says.

But Steff, who has a 12-year-old daughter with Down syndrome, says one of the biggest barriers to that happening is low expectations. Society generally has a poor understanding of how people with the condition – about 270 are born in Australia annually – live their lives. One consequence is that more than 90 per cent of pregnant couples decide to terminate in cases where prenatal testing indicates a high chance of Down syndrome, he says.

While the organisation is not opposed to terminations, he says people need to be properly informed. Surveys in 2017 of parents of children with Down syndrome recorded that half of the families said they had felt pressured to terminate by medical providers, while in almost 70 per cent of cases, they had felt they were not given an understanding of the lived experience of people with the condition.

Awareness of that has slowly improved, Steff says, thanks to organisations like Restless which provide opportunities for, and have high expectations of, people with Down syndrome. “It’s powerful,” he says. “It’s really only by things happening at all levels – organisations like this, systemic change in the policies at government level – that we’re going to slowly chip away at that community attitude.”

Ryan does not wish to buy into any debate about terminations. “I just think, from what I’ve observed, and it really depends on the person’s situation, that I’ve seen our dancers having a fulfilled life,” she says. “And the interesting thing is sometimes they don’t see themselves as disabled. Like, Charlie is a champion swimmer. At the same time, I think what Restless is really important for is that it can change not only public perceptions but family perspectives. I had this most beautiful … it was the best comment I’ve ever heard from anyone, in a way. Michael [Hodyl’s] father rang me and said, ‘I just want to tell you that I woke up this morning and Michael was all ready to come to Restless and he was vacuuming – and he’s never vacuumed in his life’. And he said to me, ‘So Michael now has a purpose in life, and that is to be a dancer’. And I just went, ‘Oh, my God’. I mean, that’s the most rewarding kind of – comment I could ever get.”

When it comes to help, though, it is not one-way traffic.

While Ryan’s diagnosis of MS has now shifted to neuromyelitis optica, which typically affects the optic nerves and spinal cord, her overall health has been stable for some time. Emotionally though, it has been tough. In the past three years she has lost her father, mother and one of her three brothers, Gary. She also feared she would lose the dance company.

Since Ryan has a big smile and frequent machine-gun laugh, the pain is not obvious. “I still feel sad about everything,” she admits. “I can’t escape that, but I couldn’t imagine surviving without the people I have around me, because I don’t have my own family in South Australia. To come back here [after my mother died] and then to go into the rehearsal room, and some of the dancers didn’t say anything, they just came and gave me a hug – I can tell you, that warmed my heart, and I just went, ‘I’m going to be OK’.”